Hot Springs National Park covers an area of 22.5 square kilometers (9 square miles) or 2,250 hectares(5,550 acres).

The park is centered on 47 thermal springs, from which more than 3,200,000 liters (850,000 gallons) of water, with an average temperature of 62°C (143 °F), flows daily.

The springs emerge in a gap between Hot Springs Mountain and West Mountain in an area about 460 meters(1,500 feet) long by 120 meters(400 feet) Wide at altitudes from 176 to 208 meters(576 to 683 feet).

The water all comes from the same deep source, but the surface appearance of the springs differed.

In addition to the hot springs, the park encompasses a wilderness area with over 32 kilometers (20 miles) of trails and a campground.

The park includes portions of downtown Hot Springs, making it one of the most accessible national parks.

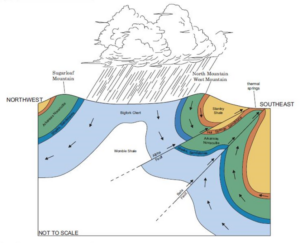

Hot Springs National Park is found within the Zig-Zag Mountains, a section of the Ouachita Mountains of central Arkansas and eastern Oklahoma. The name “Zig Zag” comes from the sharply angular folds of the rock when seen from above. The Ouachita Mountains were formed during the collision of two tectonic plates around 300 Ma (million years ago), which is called Tectonic Orogeny, or a mountain-building event. As these tectonic plates collided, the layers of rock were bent and broken. This deformation of the rock layers created cracks in the rocks. When water falls as rain on the mountains, it can seep into the ground.

The area of the park is characterized by steep, mountainous terrain. Although once more jagged, the time has reduced the steep peaks of ancient mountains into more gently rolling hills. Visitors will notice that rock layers exposed along bluffs or roadcuts appear to be tilted, or even to stand up straight, rather than lay flat. This tilting of rock layers is a result of extreme forces that “pushed” the rocks into the tilted position, which we can observe today.

The rocks found within the park are approximately 400 million years old and are mostly sedimentary in nature. Rocks like Sandstone, Shale, Chert and novaculite were originally formed in the deep ocean environments of the carboniferous period.

The temperature in the Earth increases with depth below the surface, something is known as Geothermal Gradient. The deeper that you travel towards the Earth’s core, the hotter the rocks become.

Remember the Folds and Faults formed during the building of the Ouachita mountains? They create a route that allows rainwater to travel down 6,000 to 8,000 feet below the surface, slowly heating up as it travels deeper and deeper. The water travels for 4,000 years before hitting a fault line and relatively quickly, or about 400 years, reaching the surface in what is now the historic downtown area of Hot Springs National Park, along Bathhouse Row.So, in short, when rain falls on the recharge zone, it follows the faults and cracks to a depth of 8,000 feet and then re-emerges approximately 4400 years later, at an average temperature of 143° Fahrenheit (62°Celcius).

The hot water that emerges at the park contains a variety of dissolved minerals that come from the water’s interaction with rocks both deep within and near the earth’s surface. Much like dissolving sugar in sweet tea, the hot water dissolves some of these minerals from the rocks, bringing them to the surface. These minerals include silica, calcium, calcium carbonate, magnesium, and potassium.Of these, one of the most noticeable minerals is calcium carbonate. When the hot, thermal water reaches the surface it cools. As the cooling occurs, calcium carbonate, also known as limestone, is deposited. Visitors will notice light grey, “spongy” looking rocks near some of the park’s display springs, especially at the Hot Water Cascade on Arlington Lawn. This limestone rock is also referred to as tufa.

The most common topographic features of the park are the rocky mountain slopes with their novaculite outcrops and lush creek valleys. These areas support mixed stands of oak and hickory interspersed with shortleaf pine on the more exposed slopes and ridgetops. The forest understory contains flowering shrubs, a wide variety of wildflowers, a rare local chinquapin species, and occasionally the rare Graves spleenwort.